Written by Joi Misenti, third year Integrative Biology major.

The study of science demands diligence and discipline. This truth stands resolute even in the realm of creative expression. Wildlife artists, though artists at heart, pledge themselves to an oath of accuracy, scientific veracity, and representationalism. Through my research work on the collections of Allan Brooks, I gleaned the devotion with which the core values of proper scientific work were upheld. I found those rigorous qualities incorporated into his paintings in striking, resplendent, and beautifully textured ways. He captured the wispy movements of foxes, the delicate plumage layers in bird feathers, the curiosity that gleams in otter eyes, and importantly, the backdrop against which all this faunal secrecy took place. It was this true portrayal of landscape alongside accurate subject matter that exemplified Brooks’ principled approach and set him apart from colleagues of his time.

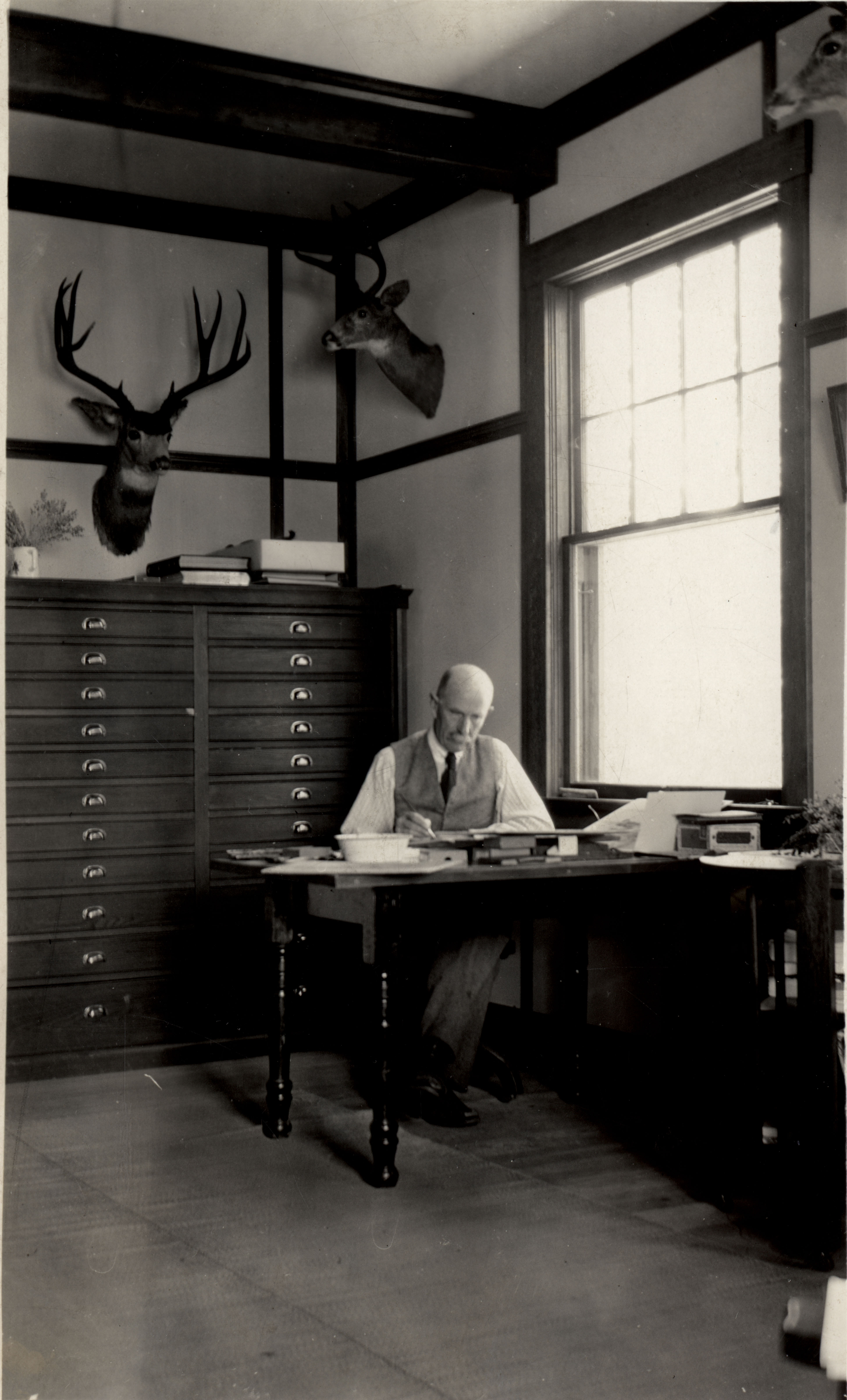

Allan Brooks not only experienced an illustrious career, but he led an incredibly colorful life. English by heritage, Brooks was born in northern India in 1869 before being sent to England for schooling at the age of 4. However, he only remained in England for 8 years before the family uprooted to Canada, where Brooks discovered the country he would call his home. By this time, Brooks was well underway to nurturing his passion for ornithology, specimen collection, skin preparation, and sketching. He had already begun to make ripples as a wildlife illustrator when World War I splashed to the forefront. Brooks promptly enlisted in 1914 and distinguished himself as an exemplary sniper, earning a medal for his service. Upon returning to Canada unhurt, save for a new disenchantment with hunting, Brooks resumed his work and engrossed himself in his projects. It was during this time, the 1920s, that Brooks rose to prominence as a premier wildlife artist in demand. He came into association and friendship with the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology’s very own Joseph Grinnell, the museum’s first director, as well as Harry Swarth, the museum’s curator of birds.

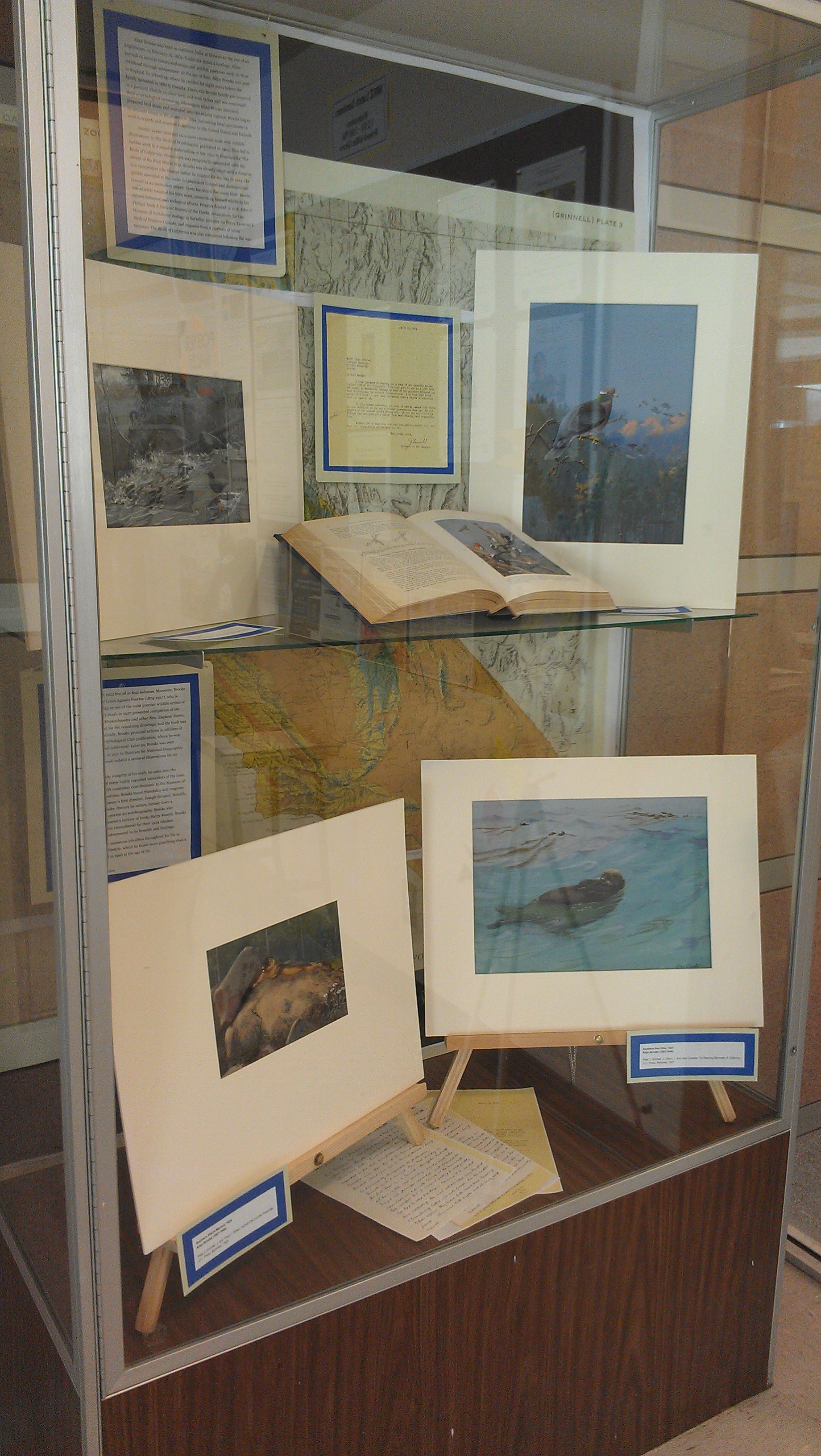

Perusing through the letters that Brooks exchanged with Grinnell, Swarth, and other contemporaries, I was illuminated by the manner of correspondence characteristic of the time period. Extensive, painstakingly written letters exchanged with detailed accounts, transactions, and lists, in addition to pleasantries. Moreover, these letters were sent dutifully and often. I realized these documents stood as a testament to scientific collaboration, experts in various fields consulting one another, providing resources and information, down to debating scientific names. I was endlessly amused by how the idiosyncrasies of the correspondent inevitably surfaced through the page. Grinnell would implore Brooks to pen a biography, an offer which Brooks would–true to his modest nature–turn down, citing that he couldn’t be trusted to complete such a promise. Occasionally, Brooks and Grinnell poked jabs at a mutual nemesis, chortling amongst themselves in a manner not unlike those of snickering schoolchildren.

Indeed, I was entranced by these historical treasures. Immersed in the letters, I shared in on these inside jokes, sensed the urgency underneath some of the requests, and felt the wonderment expressed at the sight of some elusive animals. Through the paintings, I became awed by the meticulousness and skill Brooks wielded over his craft–the countless hours of observation, the preliminary sketches, the transcription of even the slightest detail. This wonderful experience has been incredibly multifaceted and far-reaching, even culminating in an Allan Brooks display on Cal Day that justifiably gives a talented artist deserved recognition. Ultimately, I hope others will stumble across the art of Allan Brooks and find themselves equally suspended with disbelief at his masterful encapsulation.

Joi Misenti published the Finding Aid to the Allan Brooks papers on the Online Archive of California as part of her project with the MVZ Archives.

Related Links: http://www.abnc.ca/index.php/gallery http://www.vernonmuseum.ca/cr_allan_brooks.html