Written by Alessandra J. Moyer, fourth year, Integrative Biology

Part III: Patwin

In the 1920s and 30s, when Grinnell, Dixon, and Linsdale in the MVZ were puzzling over the Sacramento Valley red foxes, there was no way to adequately determine the true origin of the unusual population. But the unanswered question was not forgotten…

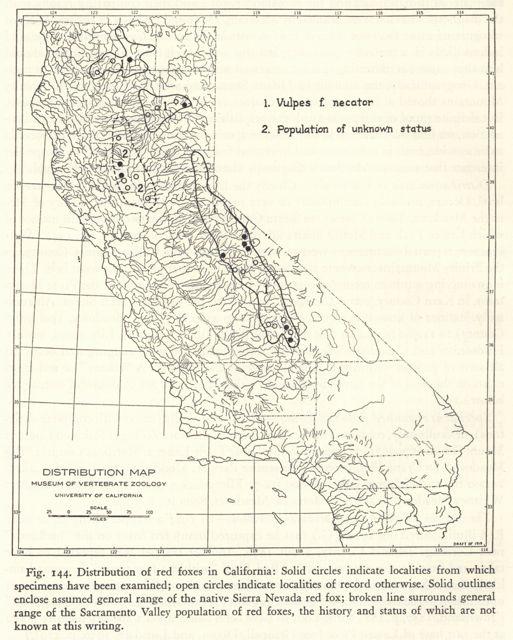

Recently, with molecular techniques unimaginable in Grinnell’s time, Dr. Benjamin Sacks and coworkers at UC Davis reexamined the story of the red fox. They looked at museum specimens, including the MVZ holotype, as well as modern specimens for each of the native West Coast groups (Southern Cascades, Northern Cascades, Rocky Mountains, Sierra Nevada), as well as the Sacramento Valley group, the San Joaquin Valley group, and a selection of Eurasian red foxes. The San Joaquin Valley group was known to be nonnative, derived from Alaskan and Canadian stock brought to California for fur farming. The scientists looked at sequences of DNA isolated from the specimens to determine which groups were most related to each other and to estimate the effective size of the populations. What they discovered was that the Sacramento Valley population was most closely related to the native Sierra Nevada population (Vulpes vulpes necator), even though it is most geographically close to the exotic San Joaquin population. They found no evidence to support the hypothesis that the Sacramento Valley population was derived from European stock that was transferred to California from the Midwest in the 19th century (“North American Montane” 1536).

The authors of the study felt that the Sacramento Valley population, though genetically closely related to the Sierra Nevada population, shows such substantial differences from the montane population in terms of ecology that it should be considered its own subspecies. They proposed that the red fox of the Sacramento Valley be called Vulpes vulpes patwin. “Patwin” is the term used to refer to several Native American tribes that formerly inhabited the Sacramento Valley.

The findings of this study are significant for conservation because V. v. patwin is now considered a separate, native subspecies with a population size small enough and fragile enough to warrant a designation of “California State Species of Special Concern.” Its rural grassland habitat is also in jeopardy, as it continues to be converted to irrigated agricultural land (“Native Sac. Val. red fox” 2). The native foxes’ preference for arid grasslands shows an important difference between the patwin subspecies and non-native red foxes in California. Exotic foxes, which frequently do make their dens in wetlands, can be a threat to endangered ground-nesting birds.

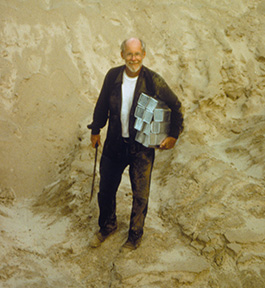

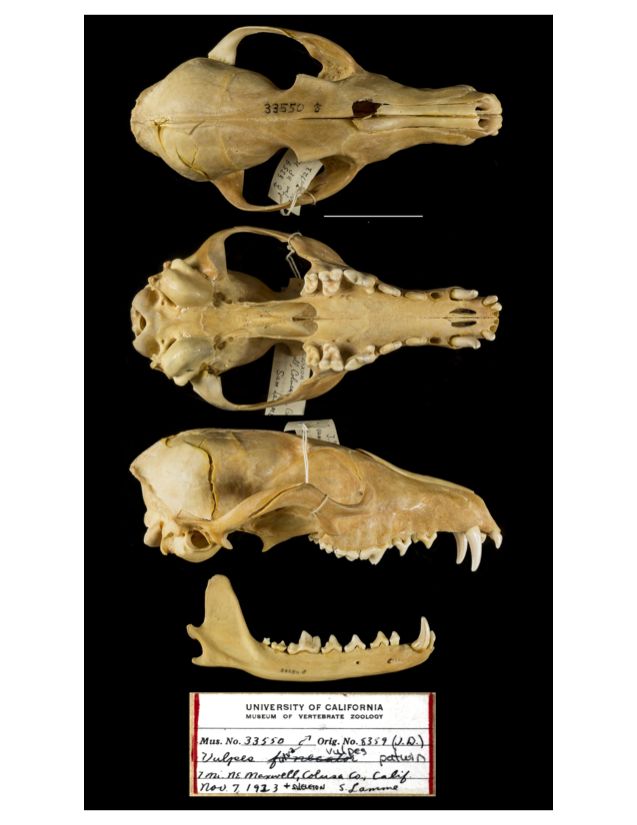

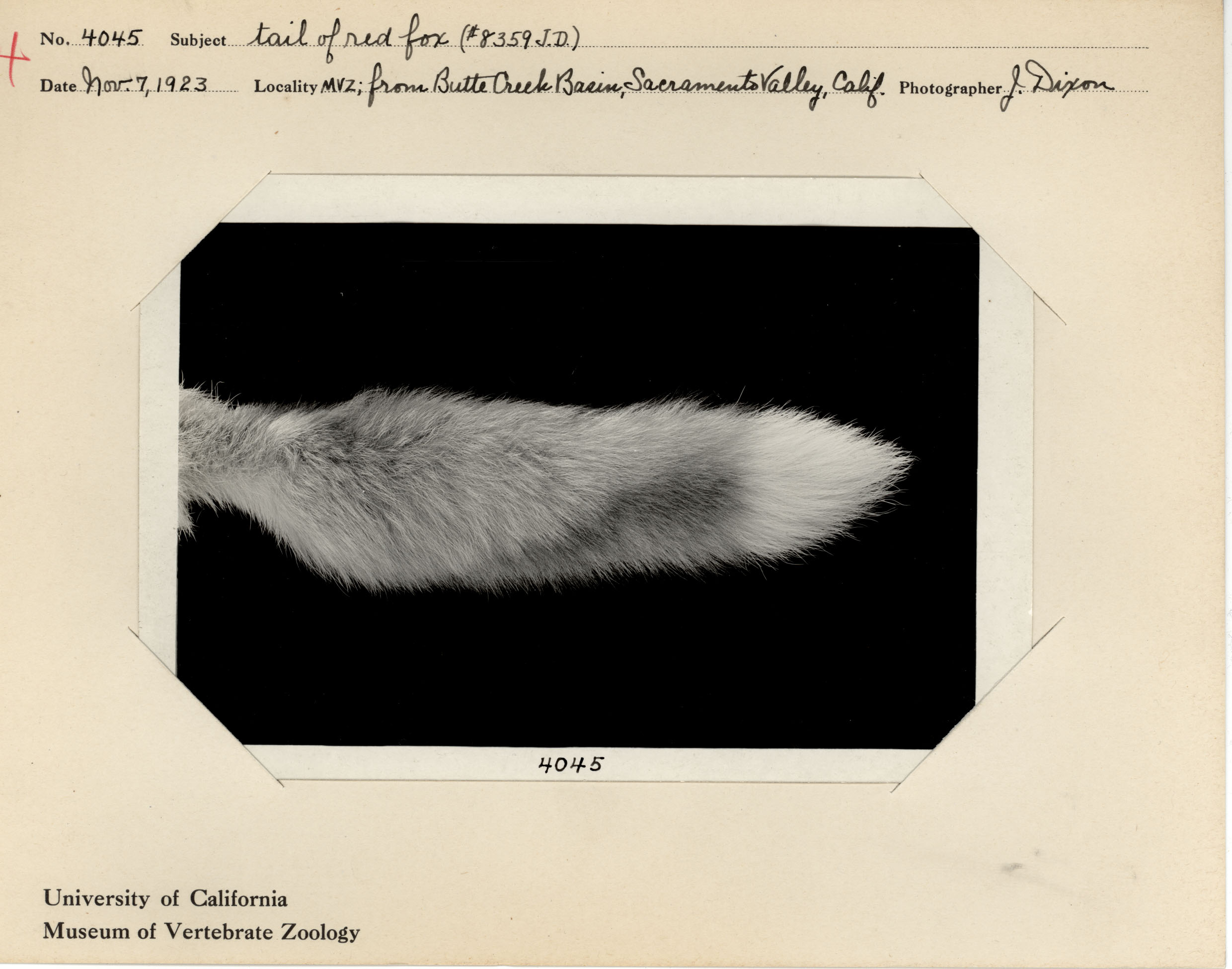

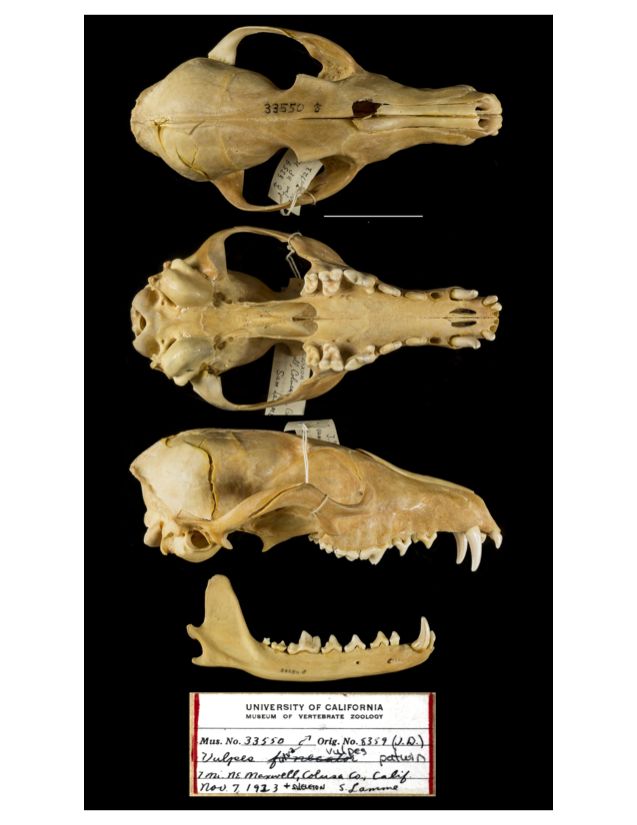

Skull of Vulpes vulpes patwin (MVZ Mammal #33550) collected by Sam Lamme on November 7, 1923, from Colusa County, California.

Now that the Sacramento Valley population has been designated its own subspecies, the the skin and skull of the young male fox at the MVZ is officially a holotype. His arrival at the museum back in 1923 prompted an investigation into his kind that has only just been concluded. And, in fact, questions still remain. In their report to the California Department of Fish and Game, Sacks, Wittmer, and Statham bring up the uneasy relationship between coyotes and red foxes. Generally, the presence of coyotes discourages the presence of red foxes. In recent times, the Sacramento Valley red foxes seem to have found some protection from coyotes by living in the vicinity of human-built structures and domestic dogs (“Native Sac. Val. red fox” 17). The authors open the question of how, historically, this red fox population dealt with coyotes. They suggest that while dogs associated with Native American groups may have provided some protection, this ecological dynamic may be a reason why the Sacramento Valley subspecies is larger on average than the Sierra Nevada subspecies. As always, more studies are needed.

References:

Sacks, Benjamin N., et al. “North American montane red foxes: expansion, fragmentation, and the origin of the Sacramento Valley red fox.” Conservation Genetics 11.4 (2010): 1523-1539. Springer Netherlands. Web. 6 July 2014.

Sacks, Benjamin N., Heiko U. Wittmer, Mark J. Statham. The Native Sacramento Valley red fox. Report to the California Department of Fish and Game. 2010. Web. 6 July 2014. <http://foxsurvey.ucdavis.edu/documents/30May2010_FinalReport_ForDistribution.pdf>

“Sacramento Valley Fox Survey.” UC Davis. U of CA, 12 Dec. 2013. Web. 6 July 2014.

Related Links:

You can see UC Davis’s Sacramento Valley Fox Survey page here, including details about Phase II of the survey, which is currently in progress: http://foxsurvey.ucdavis.edu/