by Jackie L. Childers, MVZ graduate student

One of the major undertakings of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology’s (MVZ) Archives project is digitizing historical photographs. This includes maps, images of specimens and landscapes, as well as portraits of some of the MVZ’s founding members whose legacies are written all over the walls and corridors of the museum itself. Of course, any one who has ever passed through the MVZ is familiar with the name Annie Montague Alexander. For those who are unfamiliar with her name, she was the second eldest daughter of Samuel Thomas Alexander, who was instrumental in establishing what would later become the California and Hawaiian Sugar Company (C&H). An heiress to her father’s sugar empire, Alexander used her philanthropic power to establish both the UC Paleontology Museum and UC Museum of Vertebrate Zoology on the Berkeley campus. As a founder and lifelong patron, her vision was to make both museums leading hotspots for natural history research in the western United States by emphasizing field work, exploration, and specimen collection and preservation. While many are familiar with Alexander’s philanthropic legacy, few are aware of her many scientific contributions to the museum. This includes the numerous field expeditions to Alaska and the southwest U.S. that she personally funded, and the resulting 6,177 bird, mammal, reptile and amphibian specimens that she collected during them. That this aspect of her life remains virtually unknown comes as no surprise, as Alexander detested the public eye and preferred instead to work in anonymity. For instance, she rebuked any offers to have any campus buildings or structures named after her or in her family’s honor, as was commonly done for other early university donors such as Phoebe Hearst and Jane Sather. Additionally, despite her abilities as a naturalist and field biologist, she preferred not to be included on scientific publications despite the insistence of her peers, and only begrudgingly allowed a single portrait of herself to be taken for the museum, under the agreement that it would only be displayed publicly in the gallery after her death.

Given her private nature, I was both surprised and thrilled to come across a series of photos from Alexander’s 1904 expedition to British East Africa. Much more than just a typical safari, I would later find that this trip had a profound impact on her life, both positively and negatively. Moreover, this experience would ultimately serve as the catalyst for her founding of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology four years later. Prior to the expedition Alexander had begun kindling her interest in natural history research by auditing courses taught by the renowned paleontologist John C. Merriam at UC Berkeley. With his encouragement she eventually began participating in fossil digs in sites around California, solidifying in her an emphatic love of field work. At a time when women didn’t possess the right to vote, much less pursue scientific endeavors, such activities were extremely unconventional. However Alexander’s father Samuel was a progressive spirit and an avid outdoorsman himself who encouraged his daughter to pursue her academic interests unrestrictedly, ultimately shaping her own independent and determined nature. Thus it came as no surprise to those close to Samuel that upon organizing his first trip to Africa, he announced that he intended to bring Annie along with him. Reviewing his correspondence with friends and family members during this time, it is clear that his daughter possessed his full confidence in terms of her ability to endure the physical demands of the trip.

“An Austrian Count returned about two weeks ago from a shooting trip with nine lion skins. He came, however, in one case, very near being killed. If it had not been for his brave gun carrier, who brained the lion when it was on top of him, he would have been killed. I have the same gun bearer, and if he cannot handle the lion I know that Annie will seize it by the tail and sling it 20 ft. away.”

-Samuel T. Alexander (May, 1904)

A portrait of the Alexander family taken in Hawaii in the 1880’s, prior to their move to Oakland. Samuel Alexander sits on the far right with Annie standing behind him (photographer unknown; image from Williams, R.M., 1994. Annie Montague Alexander: explorer, naturalist, philanthropist. Hawaiian Journal of History 28: 155.)

The trip commenced in early April 1904 when father and daughter, aged 67 and 36, traveled by boat from New York to Europe. From there they boarded a German steamer, the Kanzler, from a Dutch port and landed in Mombasa, British East Africa (present day Kenya) more than a month later. Upon arriving they began gathering supplies, hired a team of porters, and soon the entire party, which by this point numbered nearly 70 people strong, set out on their proposed 780 mile trek across what is now Kenya and southeastern Uganda. During the first part of the trip Annie and Samuel would spend their days hunting, returning in the evening with whatever animals they’d collected, which they would then deliver to their cook to prepare for supper in the evening. Despite being constantly subjected to numerous bodily discomforts, such as the nightly barrage of mosquitos and the sweltering heat of the day, Alexander seemed to thrive in this wild setting. In many ways this untamed environment reminded her of her childhood days spent growing up and exploring the lush and biodiverse tropical forests of Hawaii. It wasn’t until she turned 14 that Samuel moved the family to Oakland, where quickly she began to realize that she was not suited for city life. Instead she found the urban setting oppressive, as it seemed to restrict her access to the outdoors and left her eagerness for adventure unfulfilled. However, here in the African wilderness, all of the stresses and anxieties that the city had inflicted upon her back home appeared to dissipate with each passing day. During this time Samuel would write to his wife,

“Annie seems to flourish in this heat. She has a fine appetite, sleeps well & can stand any amount of tramping.”

later adding,

“I have never seen her in better health. I am afraid this sort of life suits her too well.”

Base camp near Nakuru, Kenya (June 1, 1904; photo by Annie M. Alexander, courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. MVZ image no. 6017)

While the primary purpose of the trip was to acquire hunting trophies, Alexander also sought to develop her skills as a photographer by documenting the native animals and plants that she encountered daily. Inspired by the naturalist and wildlife photographer Ernest Thompson Seton, Alexander was eager to experiment with his method of observing animals through the camera lens in order to gain a better understanding of their natural habits and behaviors. Bringing three large, bulky cameras with her, as well as all of the supplies and necessary equipment she needed to develop her film in the field, Alexander would eventually take hundreds of photographs during their travels. During the day Alexander would take opportune photos of the immediate plants and animals that she happened upon, and in some instances when her subject was more skittish, she would sit and wait patiently for the right moment to snap a candid photo. Following this she’d spend the early morning hours developing her film at camp. A year after her return the San Francisco Chronicle would eventually publish an article about the expedition, noting that her photographic series constituted the most complete documentation of that particular region of Africa to date.

Samuel Alexander with a Jackson’s Hartebeest, near Nakuru Kenya (June 1904; photo by Annie M. Alexander, courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. MVZ image no. 6019).

By August the party had traveled hundreds of miles across Kenya into present-day Uganda, spending their days hiking and searching for local wildlife, while nights were spent listening to the deafening roars of lions by the fireside (which they made sure to keep well lit throughout the night!). After months of traveling they had accrued dozens of skins and had even encountered a rhino, though their attempt to hunt it had been terribly unsuccessful. Yet as the trip began to draw to a close Samuel found himself unsatisfied, for despite their efforts they had yet to encounter the largest and most exotic of the African beasts- the African elephant.

While returning to Mombasa, father and daughter stopped at the village of Kijabe to visit the Hurlburt’s, an American missionary family stationed there. Under the insistence of Mr. Stauffacher, a local guide and assistant to Mr. Hurlburt, they decided to set up a tent in Mr. Hurlburt’s yard in order to have one final attempt at encountering an elephant. This decision proved successful, as the following morning the trio found themselves face-to-face with fresh elephant tracks along their path. Suddenly without warning, eight to ten elephants came crashing through the trees right towards them. The following is an excerpt from “On Her Own Terms” by Barbara Stein:

“With no place to run the trio froze behind a tree, stunned as the herd suddenly parted in their midst, some animals veering in one direction, some in another. The amazed hunters were unscathed and, seizing the moment, they took aim. Amid a flurry of bullets, a midsized bull with tusks a bit over 4 ft in length slumped to its knees.”

The three are shown here atop the elephant, Samuel sits on the far left, Mr. Stauffacher is on the right, with Annie in the middle (August 4, 1904; photographer unknown, courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. MVZ image no. 6018).

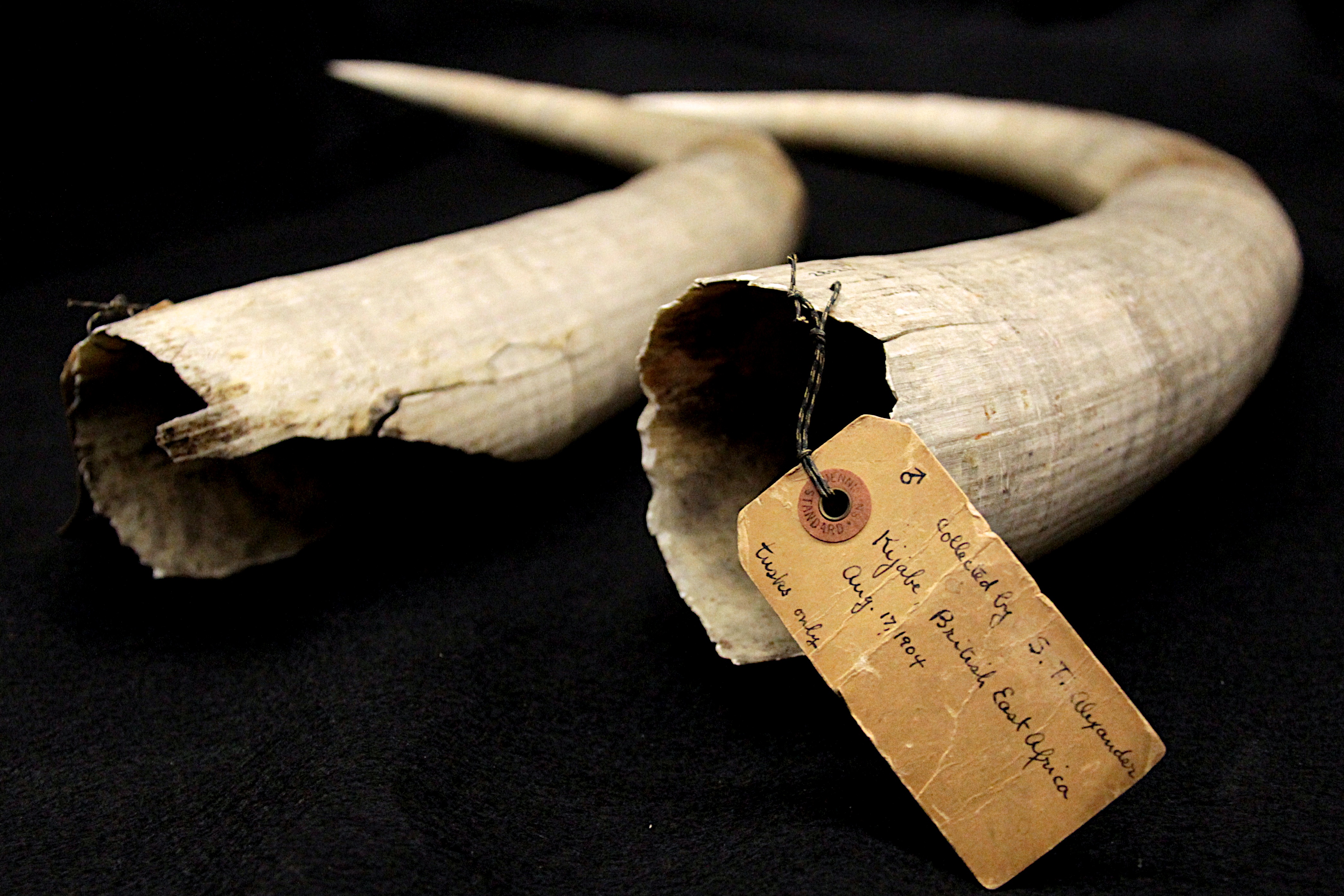

The above image is one I discovered while cataloging photos for the MVZ Archive’s this past summer, and what initially prompted me to write this piece. While today such images would most certainly be viewed in poor taste, it is important to keep in mind that during this time modern concepts of wildlife conservation did not exist, and that populations of large African mammals such as elephants were not nearly so depauperate as they are today. As I stared with curious fascination at this photo, it suddenly dawned upon me that we might actually possess specimens from this expedition. I immediately searched the museum database and lo and behold, tusks from a Loxodonta africana collected in Kijabe, Kenya in 1904 existed in our collection! Moments later I found myself wandering around the MVZ’s bone collection, peering across the shelves as I searched for the proper label. Finally I spotted them. I reached out my hands and touched the smooth ivory, soon discovering the old, weathered specimen tag that possessed Samuel’s initials. As I stood peering down at them I contemplated how amazing it is that these tusks passed through the hands of both father and daughter, and successfully traveled nearly 5,000 miles from Kenya to Berkeley at a time when airplanes had not yet been invented. Now over a hundred years later, these tusks remain in pristine condition, possessing all of their original scratches and depressions, providing the only evidence of an animal that once lived a century ago.

(Top and bottom) Tusks from MVZ specimen no. 28022, the bottom image shows the original specimen tag which provides the date and locality where the tusks were collected; Samuel Alexander’s initials are depicted in the top right corner of the tag (October, 7, 2016; photos by Jackie L. Childers).

Following this final hunt Alexander would write to her mother several days later from Mombasa,

“…We have made every day count. I doubt if there are two more delighted people in this country than Papa and I.”

However, the trip did not end there. From Mombasa, Samuel and Annie proceeded south to make one final visit to Victoria Falls via the German steamboat the Konig. At some point during this final leg of their trip, Samuel was suddenly struck with a grave sense of dread. He remarked to Annie that he “felt a foreboding of disaster.” Following his premonition he informed his daughter of where she might find his money and necessary tickets for their return home from Cape Town, which was scheduled in late September.

Once in Victoria Falls they spent the next two days viewing and photographing the falls from various vantage points. Then on the morning of September 9, the two embarked on a trail into the Palm Grove Ravine, a site which afforded a magnificent view of the falls from a narrow chasm. At this time work had barely begun on what would eventually be the famous 900-foot bridge spanning across the Zambesi River, connecting the areas that became Northern and Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe). Earlier during their initial descent Annie had noted that men conducting excavation work had been dumping excess debris into the ravine. Now upon arriving at the point that provided them the best view, the two suddenly became aware of small rocks falling all around them. Suddenly a sharp sound rang out from above, and all at once a three-foot boulder came plunging down directly towards Samuel. As it came crashing down it collided with another boulder, veering directly towards his left side where he was struck forcefully, subsequently fracturing his left leg and crushing his foot. Annie immediately fled for help, returning with several men who proceeded to lift Samuel out of the ravine.This task however, proved extremely difficult, and an entire hour and a half passed before they reached the summit where they were then forced to wait for a doctor. During this time Samuel continued to suffer in agony as he bled profusely. When the doctor finally arrived he immediately applied a tourniquet and instructed that Samuel be transported to his personal home, six miles away. The group desperately proceeded slowly across the difficult terrain to his house, and by the time they arrived Samuel was barely responsive. Following the doctor’s decision to amputate Samuel’s left leg, Alexander remained by her father’s side throughout the night in the hopes that he might reawaken. However by the next morning, September 10, at 2:30 a.m., he had died. That same day a funeral was held and Samuel Alexander was buried in the Livingstone cemetery, several miles from Victoria Falls. Two days later Alexander informed her family of Samuel’s passing by cable, and then began her nearly month-long journey back home, alone. Not surprisingly, the sudden loss of her father had a profound effect on Alexander, personally and later, professionally.

“We can only guess at the tremendous sense of loss and disorientation that Alexander felt in the wake of her father’s sudden death. In a society where women were expected to marry, raise a family, and remain subservient to men in virtually all aspects of their lives, she had experienced an atmosphere of nurturing and social freedom that differed markedly from the norm. Bolstered by a financial independence available to few women of her age and time- but feeling terribly alone-she contemplated the future in a new light. Immediately, she turned to the only vocation that had given her pleasure and a sense of accomplishment in her adult life. Many years later she would write about this period, “I felt I had to do something to divert my mind and absorb my interest and the idea of making collections of west coast fauna as a nucleus for study gradually took shape in my mind.”

-Barbara Stein, “On Her Own Terms”

In the years immediately following the tragic loss of her father, Alexander worked diligently to gather the funds, personnel and institutional support to make her ambition a reality. Then by early 1908, Annie Alexander established the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology on the UC Berkeley campus, and appointed Joseph Grinnell as its first museum director. Now, over a century later the MVZ houses over 640,000 specimens of birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles, making it one of the largest natural history collections in the entire United States, and the largest of any university museum. By making primary research its central goal, it has also remained at the forefront of scientific discovery within the fields of ecology, evolutionary biology, population genetics and climate change research through the efforts of the curators, professors, post-docs and students, both graduate and undergraduate, that work within the museum. Since its inception, in many ways the original scope of the museum’s mission has broadened significantly. For instance, the advent of modern DNA-sequencing technologies eventually led to the establishment of the evolutionary genetics laboratory in 1973 and it now currently houses the MVZ’s tissue collection of well over 50,000 specimens. In addition, increased globalization has led to collaborations with international institutions and researchers, leading to the establishment of field sites in under-explored regions within Central and South America, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Australia, and southeast Asia. Despite the MVZ’s expanded scope of research, Alexander’s vision of combining field-based research with the study of museum specimens remains its central mission. By studying organisms and documenting biodiversity around the globe, MVZ scientists continue to serve an important role in broadening our understanding of the natural world and its inhabitants.

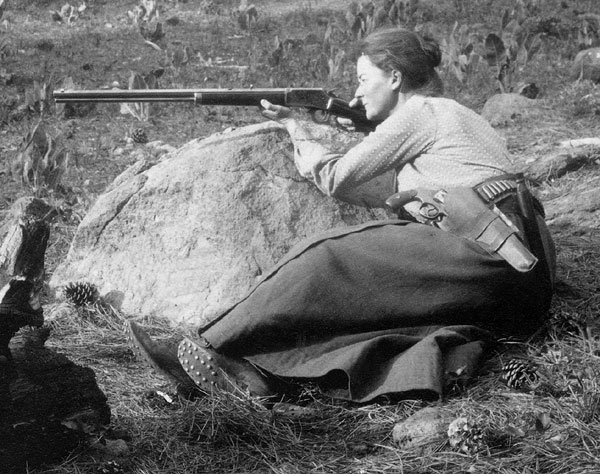

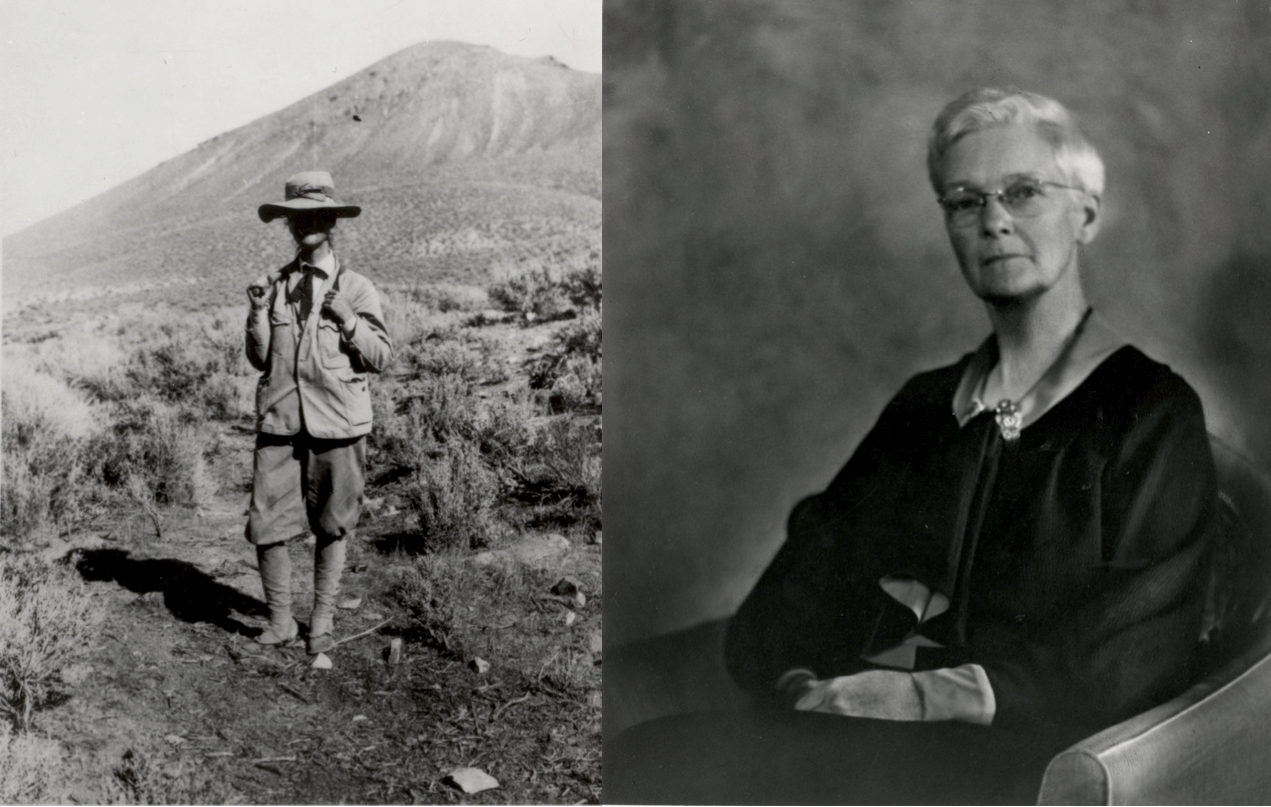

(Top) Alexander poses with her rifle on an expedition to the Fossil Lake region of southern Oregon (1901; photographer unknown, photo courtesy of the University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley); (Bottom left) At a paleontological site in the Humboldt Range, Nevada (1905; photographer unknown, photo courtesy of the University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley. MVZ image no. 6021); (Bottom right) Alexander’s portrait taken at Joseph Grinnell’s request in the fall of 1935. This portrait currently hangs in the MVZ’s gallery (MVZ image no. 6025).

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Carol Spencer, Michelle Koo, Carla Cicero and Christina Fidler for hiring me on to the MVZ Archives project this summer! It was a blast and I thoroughly enjoyed getting to rifle through and catalog so many unique and fascinating historical photographs. For assistance with photographing the featured specimen, I thank Gordon Lau and Florine Pascal. A special thanks to Benjamin Karin for dedicating his time to provide editorial assistance and comments. Thanks to my grandparents Jackie and Joe Palmquist for helping me come up with the article’s title. Finally, while some of the content needed to produce this piece was acquired directly from the MVZ Archives, the vast majority of biographical information presented was obtained from Barbara Stein’s biography “On Her Own Terms” (citation below) which not only provides a detailed account of the life of Annie Montague Alexander, but of the early foundations of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, the UC Berkeley campus, and fascinating anecdotes about the history of California as well. I highly recommended it for anyone interested in learning more about any of these topics.

–Stein, Barbara R. On her own terms: Annie Montague Alexander and the rise of science in the American West. University of California Press, 2001.

Jackie Childers is a first-year MVZ Ph.D student in the lab of Dr. Rauri Bowie. As a former UC Berkeley undergrad she worked as a curatorial assistant in the MVZ from 2009-2013, and she recently obtained a Master’s of Science in biology from Villanova University. Her research focuses on using molecular data to understand speciation processes and identify phylogeographic patterns among African birds and reptiles. She is shown here with one of the world’s coolest lizard’s, the common gliding dragon (Draco sumatranus) in Sarawak, Borneo (photo by Benjamin Karin).