Written by Alessandra J. Moyer, fourth year, Integrative Biology

Part I: The holotype

Holotype:

The single specimen (except in the case of a hapantotype,q.v.) designated or otherwise fixed as the name-bearing type of a nominal species or subspecies when the nominal taxon is established (International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, glossary).

The pale red fox skin is soft and supple, beautiful enough to grace the shoulders of any prominent society lady in 1920s California. In fact, his sibling did become a fashion accessory, but this little fox had a more unique fate. He is a holotype in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley. His skin and skull are kept with the museum’s other mammal holotypes, or specimens that were specifically used in the formal definition of a new taxonomic group.

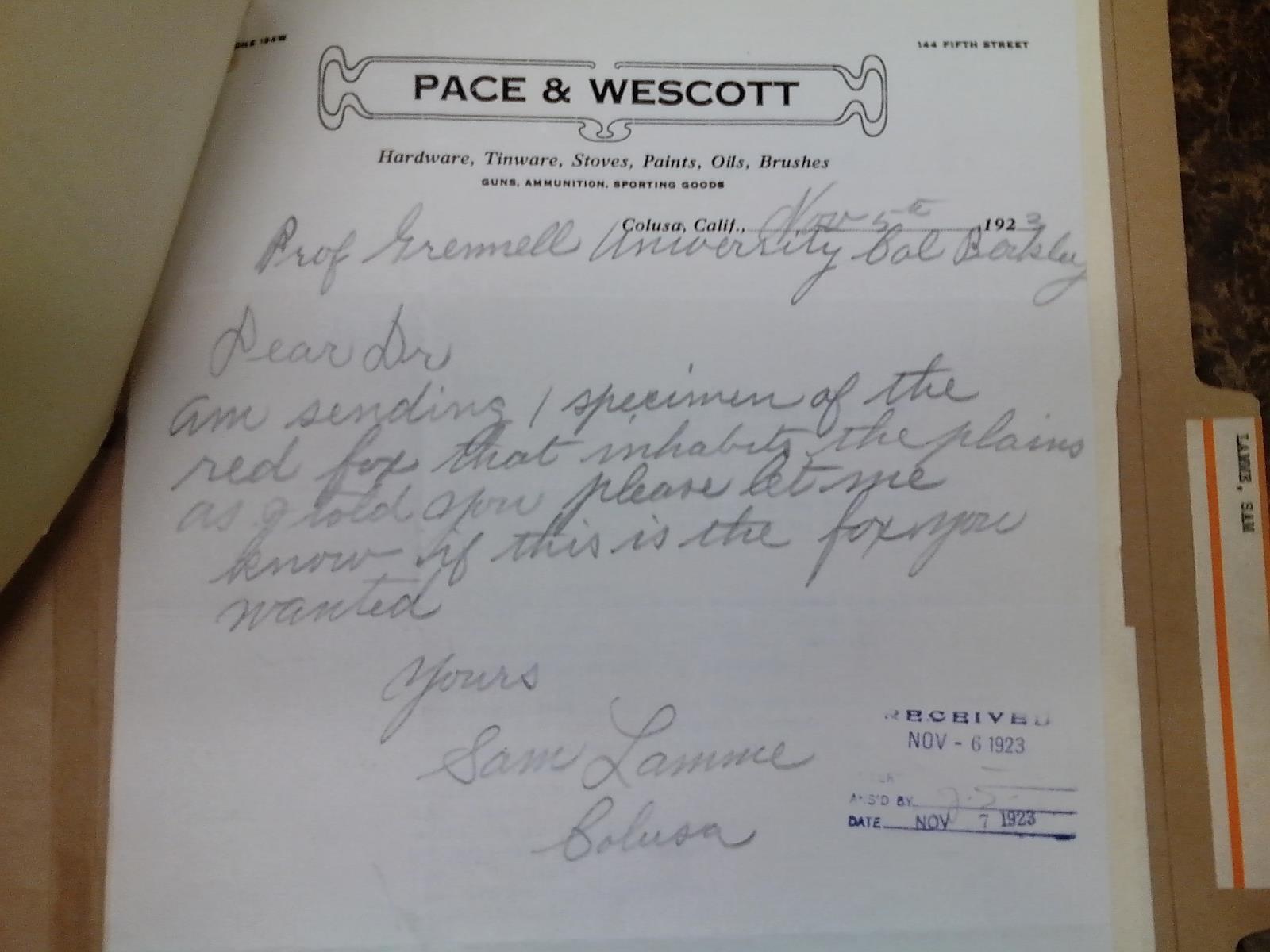

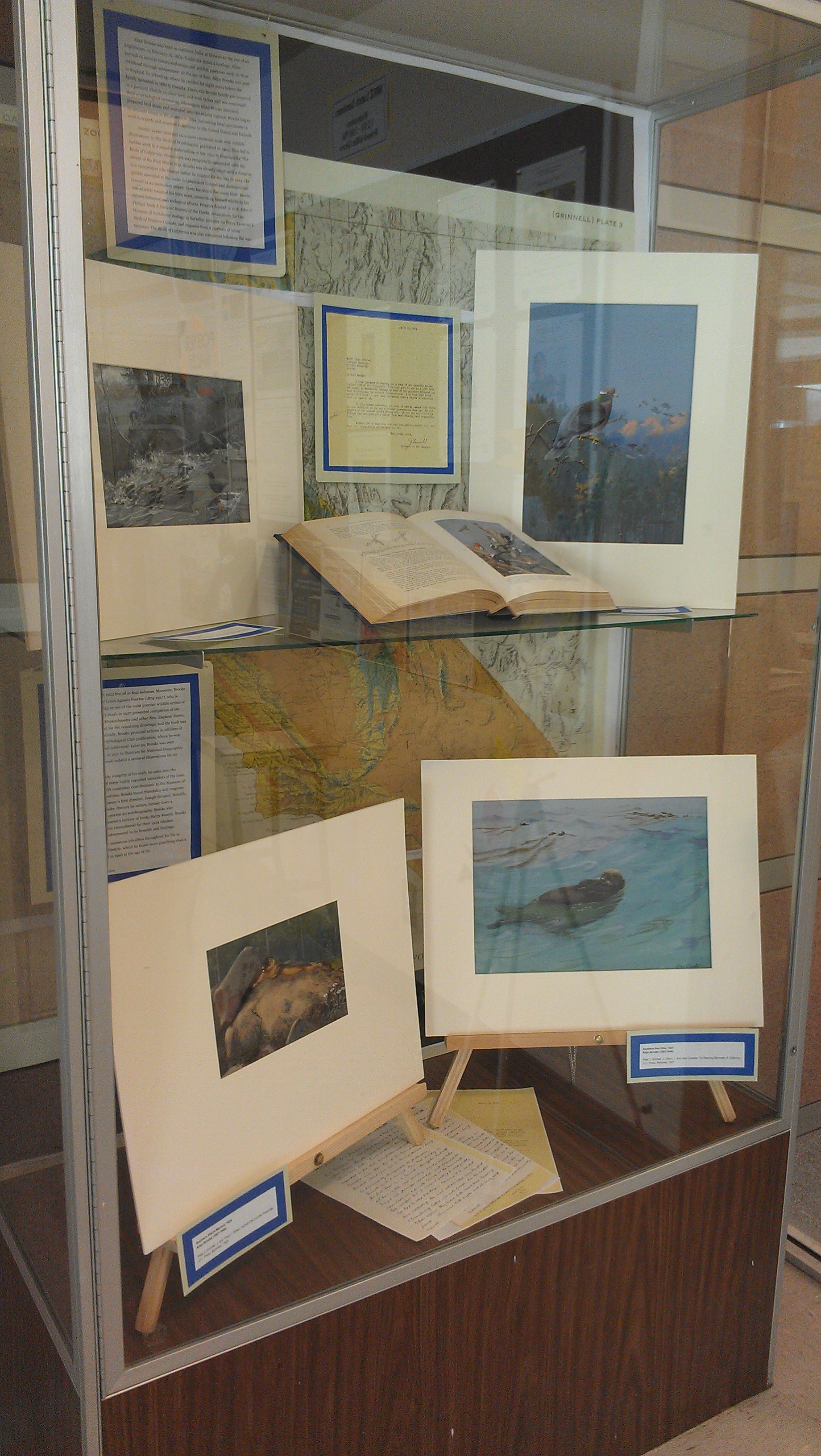

This little guy was collected in 1923, but his subspecies didn’t get a name until 2009. Why the wait? Well, nothing about this fox’s story is simple. His tale is recorded in a letter from Sam Lamme, a trapper who regularly sent bird specimens to the MVZ, to Joseph Grinnell, the first director of the MVZ. Lamme begins, “Now about the Red Fox I will give you the dope on him,” and proceeds to say that the fox was born in the spring of 1922, on the irrigated plains of Colusa County, California. He and his siblings belonged to a population of red foxes inhabiting the Sacramento plains, making their homes in abandoned ground squirrel holes (Grinnell, Dixon, and Linsdale 383). Sadly for the fox family, the litter of nine pups was “dug out” by a Mr. John Gray, who kept a few as pets. This seems to have not worked out as nicely as Gray had hoped, as the foxes soon “got killing the poultry.” Gray apparently abandoned the idea of pet foxes and they came into the custody of a man named Buck Thomas, who sold two “dogs” (male foxes) to Lamme for five dollars, which Lamme evidently considered something of a steal. Setting one aside to skin and tan as a stole for his wife, Lamme sent the other along to Grinnell at the MVZ.

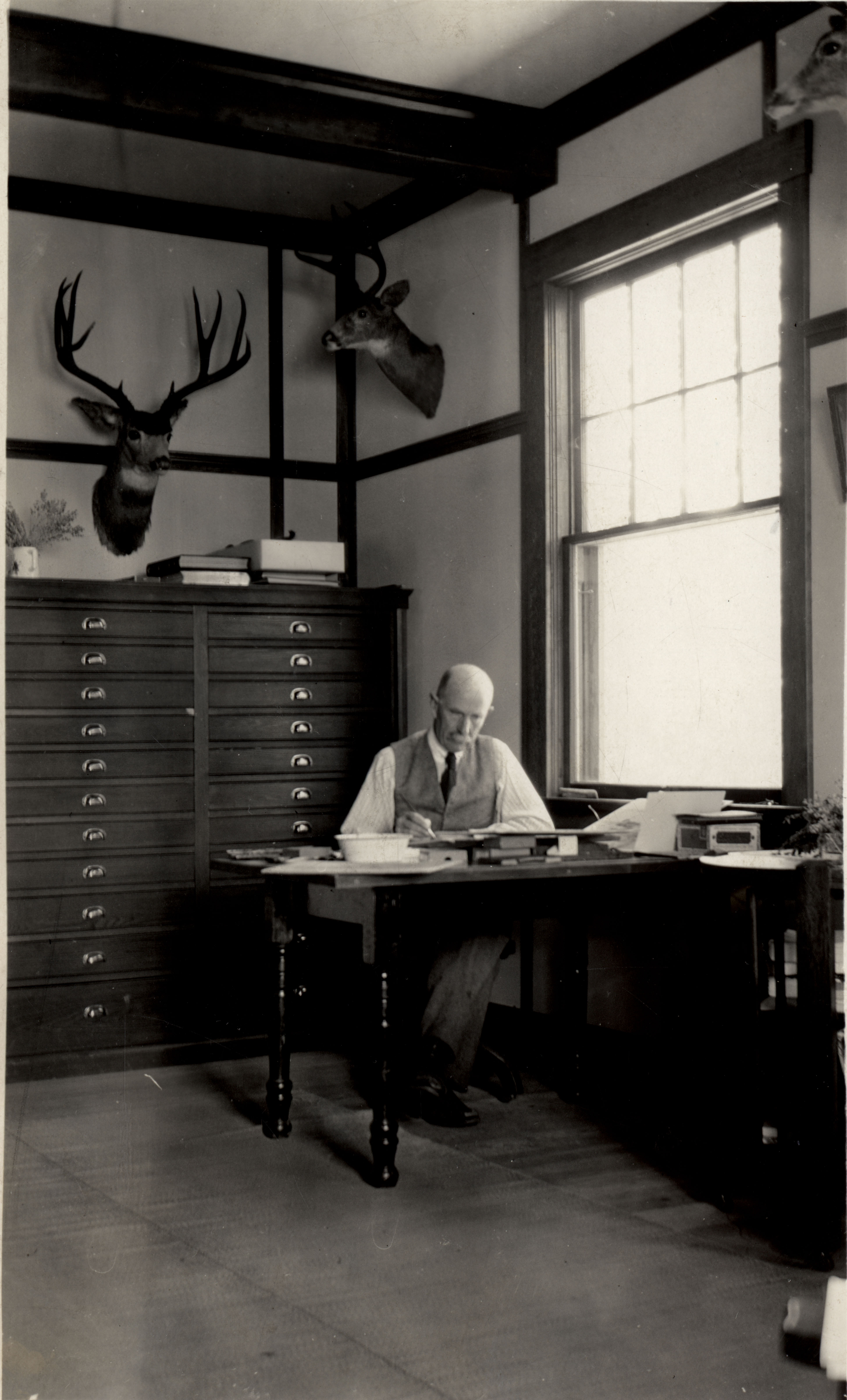

The carcass was received in Berkeley on November 7th, 1923 and subsequently prepared by Joseph Dixon, who recorded the event in his notes. He says approvingly, “This animal was very fat and in excellent condition.” Dixon also notes that the stomach contained duck feathers, of unknown species. The scientists of the MVZ were quite excited to discover the presence of the Sacramento Valley population of red foxes, which, although known to the local inhabitants, were evidently a surprise to Grinnell. He wrote several letters to Lamme after that, begging for more specimens, preferably older, and dispatched in such a way as to not inflict the kind of damage seen on the skull of the first fox (the bullet hole is rather prominent). Dixon and Grinnell were anxious to study more specimens in order to determine what the normally montane species was doing in the plains of Northern California. They soon formulated an explanation for deviant population, a hypothesis that will be explained in a subsequent blog post.

References

The Code Online. London: International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, 2012. Web. July 22, 2014.

Grinnell, Joseph, Joseph Scattergood Dixon, Jean Myron Linsdale. Fur-bearing Mammals of California: Their Natural History, Systematic Status, and Relations to Man. Vol. 2. Berkeley: U of California P, 1937. Print.

Lamme, Sam (1916-1929), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology historical correspondence, MVZA.MSS.0117, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

Volume 597, Section 2, page 32, Joseph S. Dixon Papers, MVZA.MSS.0079, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

Related Links: